SSZTCR9 april 2015

Welcome to the first post in a new series about the controller area network (CAN). Our intention with this series is to provide a well-thought-out overview of CAN, starting with the basics, and quickly get into feature details and common application questions that come up when designing a CAN network, and filling in more detail with example applications.

CAN is a distributed control, serial, two-wire differential network technology that has been around for nearly three decades. Because CAN was originally developed for automobiles, it’s a common belief that it’s only found in cars and trucks, but this is not the case. It has spread to industrial control applications such as heating, ventilation and air-conditioning (HVAC) systems; building automation like elevator control; maritime applications; white goods; and many other areas because of its robustness and simplicity.

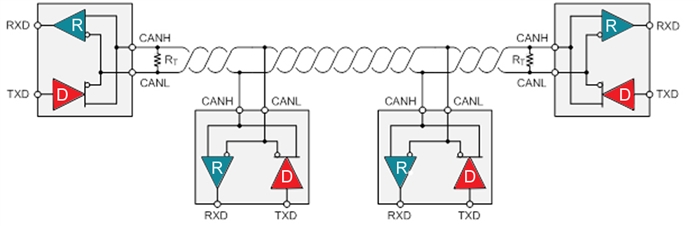

Figure 1 Typical CAN Bus

Topology

Figure 1 Typical CAN Bus

TopologyFigure 1 shows an example CAN network with four nodes. As you can see, CAN has a two-wire topology where all nodes on the network share the same bus. CAN is specified by the ISO 11898 family of standards. Like RS-485, Ethernet and many other field bus technologies, CAN is a method of distributed control that can be used in any application where microcontrollers need to communicate with each other, i.e: a sensor network for elevators.

Although the CAN standard covers the protocol layer and physical-layer requirements for communication, additional higher-layer protocols have been created to work on top of the CAN protocol like DeviceNet, J1939 and CANopen. These higher-layer protocols work to expand network lengths, number of nodes and data-payload size, while creating an organized hierarchy of identifiers.

One of the key features of CAN that makes it so easy to adopt is that the protocol handles assembling frames, arbitrating for bus access, bit stuffing, error checking, fault confinement and data synchronization. This allows the system designer to focus on application software, as opposed to having to worry about the protocol software.

In future installments of this blog series, I plan to cover the physical-layer requirements, bus-signaling levels, basic driver topology, basic receiver topology, frame formatting, termination, arbitration, the importance of two-way loop delay, error checking and fault confinement, common-mode voltage, mixing 3.3V and 5V CAN transceivers, and protection and filtering circuitry.

If there are topics not on this list that you would like to hear about, please post a comment below and I will do my best to incorporate it into future posts.