SSZTB36 July 2016 CC1310 , CC2541 , CC2650 , DRV5053 , LM4120 , MSP430FR4133 , TPS61220

In my previous blog post, I explored energy efficiency, the first of several trends in building-automation wireless-sensor networks. As a recap, the key trends driving the addition of more sensors in a building-automation system include:

- Energy efficiency.

- Safety and security.

- User comfort.

In the second part of this blog series, I’ll go over sensors, which when added to buildings can help protect users and their possessions, notify users and dispatch centers of any security breaches or notify users upon the detection of harmful conditions in the environment.

The two topics of safety and security touch a broad range of building-automation applications, from heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC), to building security, to fire safety systems.

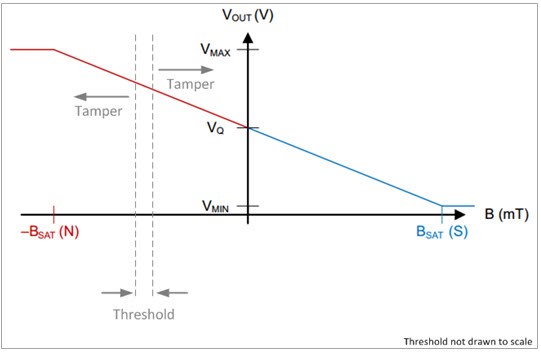

With building security systems, you may find comfort in not just having an alarm system notify authorities of irregular activities, but also giving you status updates about your home or building’s security. Today, a reed switch or digital Hall-effect sensor can help detect discrete door (or window) contact states. A duty-cycled, analog Hall-effect sensor can be used to create a more robust front end, detecting if a secondary magnet is being used to tamper with the system.

Figure 1 Analog

Hall-effect sensor with tamper detection example

Figure 1 Analog

Hall-effect sensor with tamper detection exampleWhen I was a kid, I remember my mom would start driving us to baseball practice, but turn around if she wasn’t sure whether the garage door was open or not. I fear that part of her forgetfulness has rubbed off on me. I tend to forget if I’ve actually locked my doors when I leave my home, so I will often walk back to double-check if my door is locked. With electronic smart locks, you can not only check the lock state, but also lock or unlock the door remotely.

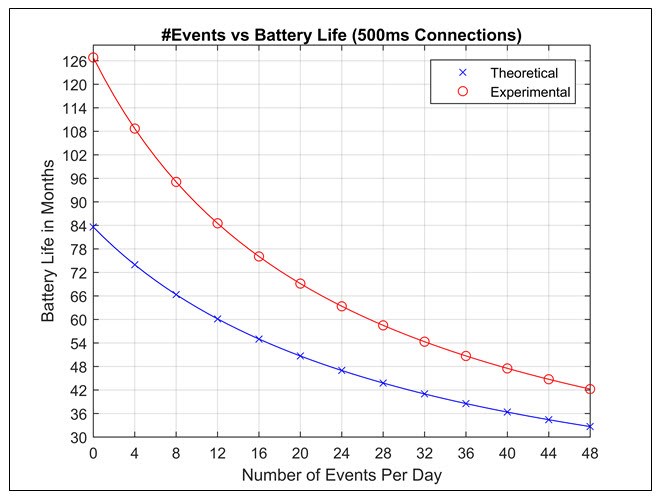

Given the number of smart wireless devices, including wireless door contacts and wireless electronic smart locks, battery life becomes a concern. The smart lock reference design enabling 5 years battery life on 4x AA batteries (TIDA-00757) demonstrates a way to increase the battery life of a 2.4GHz wireless connected electronic lock to roughly five years by using a light-load-efficient DC/DC buck converter. The designer assumed 24 individual lock or unlock events with a 500-ms Bluetooth® Low Energy connection period to determine power consumption and battery life for a 3000 mAh battery capacity.

Figure 2 Number of lock or unlock

events vs. battery life

Figure 2 Number of lock or unlock

events vs. battery lifeDetecting the state of locks, doors and windows is very useful from a building-security aspect. Shifting to safety; smoke, toxic gas or even particle monitoring are key concerns for preserving air quality for people.

Beyond audible alarms, being notified of carbon-monoxide (CO) or toxic gas (TIDA-00056) leaks or fires on a remote device can let you know if there are unsafe conditions if you are on vacation, just coming home, or a building owner. In addition to gas and fire detection, particle detection can be used to detect size and concentration for particles including cigarette smoke, dust or pollen. The TI Designs PM2.5 and PM10 Particle Sensor Analog Front-End for Air Quality Monitoring Reference Design (TIDA-00378) can give you a head start for possible ways on how to take optical-based air-quality measurements for smoke, dust or pollen particles.

For a jump-start on connected sensing, be sure to check out these building automation reference designs and the additional resources below.

Additional Resources:

- Check out these safety and security wireless-sensor-node reference designs:

- Low Power Wireless PIR Motion Detector Reference Design Enabling 10 Year Coin Cell Battery Life (TIDA-00489)

- Low-Power PIR Motion Detector with Bluetooth® Smart and 10 Year Coin Cell Battery Life Reference Design (TIDA-00759)

- MSP430FR4133 Microcontroller Air Quality Sensor Reference Design (TIDM-AIRQUALITYSENSOR)